Middle School in the Midst of an AI Revolution

As an educator and former philosophy student, I feel fairly sure that most philosophical questions and argumentative forms were generated first by children and only later stolen by academics. Middle schoolers in particular have always been on the cutting edge of questions related to the purpose of education, freedom, and justice.

- Why should I read Moby Dick if I’ll never remember it or think about it again? I mean, what was it we read last year? I’m pretty sure I already forgot.

- Why am I learning to do math my parents say they’ve never used in their lives? I think my parents make a lot more money than you do.

- Why should I make my bed? Literally no one is going to see it until I get in it again. Also look, Johnny already left without making his.

- Why can’t I sleep out on the dock? I’m sure my parents would let me. Aren’t you supposed to be teaching me to feel more comfortable and confident outdoors?

Generally, at a school with small class sizes and plenty of time for discussion, digging into these questions are some of the best parts of my day. What’s more important than teachers and students being on the same page about the purpose of education? However, some of the newest questions are stranger:

- Even if I did want to use math in life, why wouldn’t I just explain my problem to ChatGPT or write it down and put it into Photomath?

- What’s the point of learning grammar if I can literally always have an AI fix my mistakes?

- Learning to code is fun, but won’t my code be better if I have an AI write it for me?

- I feel like I might get better relationship help by just talking to ChatGPT.

And they’re not asking it directly yet, perhaps out of a misplaced sense they’ll offend me, but I feel the question coming:

- Would it be better for me to learn about this from an AI than from you?

Tougher questions. A couple years ago, I taught a language arts class on the history and future of language and thought, and we read Mo Gadawt’s book on the future of AI called Scary Smart. We dug into many of the above questions, as well as many questions about what we might be heading towards and what might be worth doing now. It was concerning, but generally, it felt great to be able to think slowly and clearly about what otherwise feels like an overwhelming force, difficult to predict and capable of upending most planning we do about the future. However, at a three-year school that rotates through language arts topics and tries not to repeat them more than once in a student’s tenure, we don’t just teach about AI all the time, and many of those students are already gone, replaced with others that have the same questions.

There’s nothing like working with a middle schooler to remind us of the importance of the here and now. Are we in the middle or just the beginning of a cultural revolution towards offloading thought itself to these digital minds we’re building? What will our place as thinkers and doers in the future be, if any? Despite reading about it constantly, I don’t know, and don’t feel convinced anyone else does either.

As individuals, we might want to alter, slow, stop, or reverse this revolution, and we may even believe that the risks posed by AI going wrong are so large that there’s almost nothing more important right now. It’s hard to know what to do with this felt importance, however. AI is being developed by many companies, mostly behind doors closed to us, and by a sector that our politicians seem to understand poorly and regulate slowly if ever. It’s not clear that even if we mustered the arguments and public outcry that led Australia to regulate social media for children, we could do much about how AI is developed.

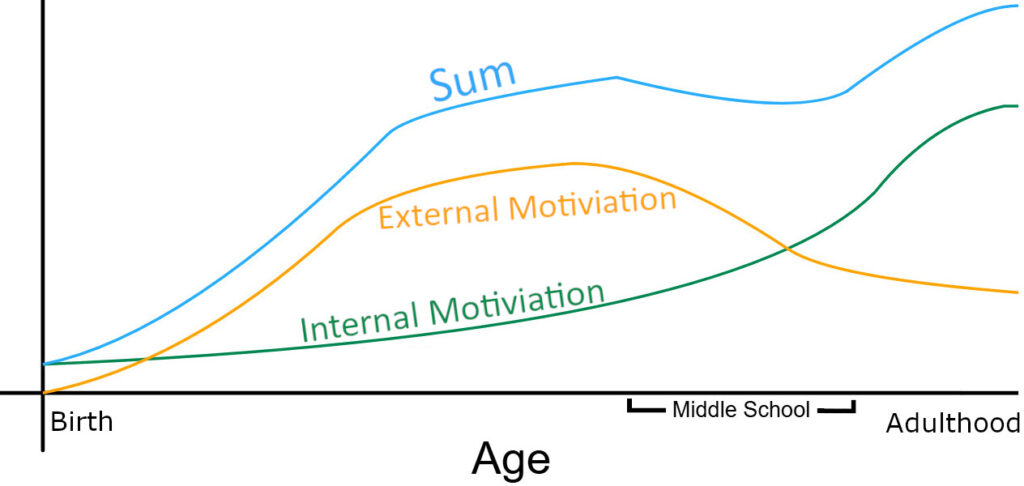

Middle school teachers often track a drop off in performance across many domains as our students stop taking external direction from adults and start trying to direct themselves with decision making skills that are just emerging. As a math teacher, I remember humoring my students by showing them this idea graphically while teaching them how to sum two functions a few years ago.

Now I wonder if the graph should be updated somehow to show the extent to which we’re all using AI to direct ourselves. Would I just increase the value of extrinsic direction across all ages? Is AI more like another parental figure in people’s life story of decision making, or more like a new part of the cultural background that’s always changing. Right now, AI influences people unevenly, depending on how much time they spend doing web searches or seeking it out specifically for advice. Some people are using it as a sounding board for every problem in their lives, and some people want nothing to do with it directly. Of course, it also affects the mechanics behind our culture profoundly, influencing present and future job availability across many fields, as well as everything to do with marketing, research, and analysis. It’s responsible for selecting and promoting almost all the digital media my middle school students talk to each other about. Increasingly, it also does the editing of this media, and it’s starting to play a more real role in its creation too. My fears about AI aren’t really in these increased forms of external direction in our lives though. What I worry more about is whether AI means the other line, Intrinsic Direction, needs to be adjusted downward. Do I still have the agency I used to in a world where AI maybe makes every decision better than me, or at least, where I maybe make most decisions more poorly if I don’t consult it? Do I start to stop making certain categories of decisions altogether because AI takes them over?

When I talk passionately about the point of our middle school program at the tiny, rural, screen-lite boarding school I work at, I tell parents about how their children will end up with so much more ability to direct themselves and get things done than their peers that they’ll be amazed. It still feels very true right now, but somehow, I feel like AI is going to start changing the meaning of that pitch soon.